Field Studies

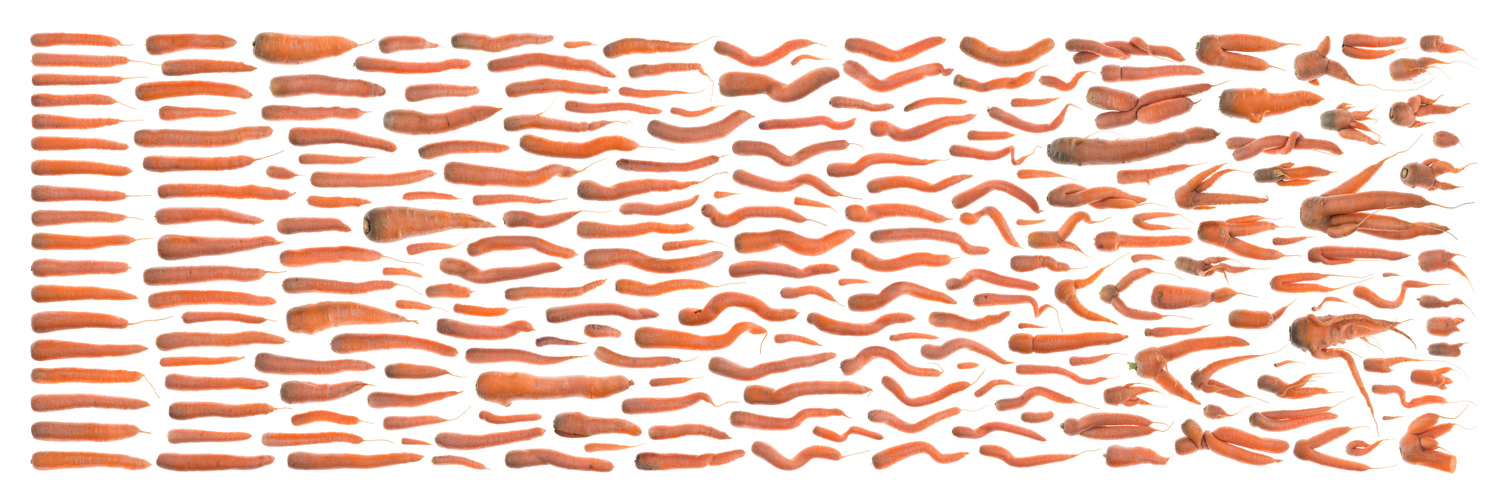

Field Study I - Prague, Czech Republic

A morphological chart of carrots harvested from a field close to Prague, Czech Republic - rejected and left to rot because they where missing their leaves.

2016 | photograph | 90cm x 270cm

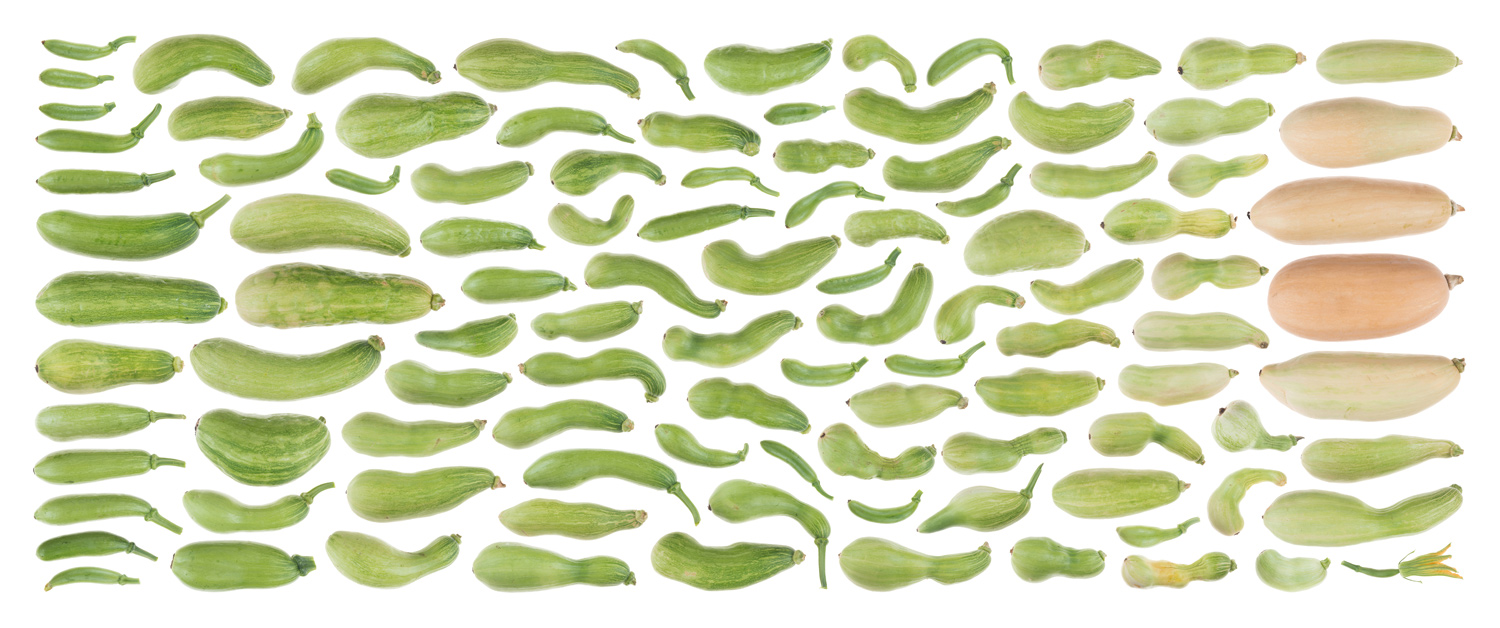

Field Study II - Seoul, Korea

A morphological chart of zucchinis harvested from a greenhouse close to Seoul, Korea - rejected and left to rot because of being of the wrong shape, size or color.

2016 | photograph | 90cm x 215cm

The text below was created in connection with the exhibition Vynikající (Delicious) by Uli Westphal at Artwall Gallery, Prague, Czech Republic (Oct 4 - Dec 2, 2016). Written by Uli Westphal and co-edited by Zachraň jídlo (2016), updated by Uli Westphal (2020).

The Decline of Wonkiness

Introduction

Fruits and vegetables that don’t fit our established norms are filtered out and avoided in every stage of our food-system. It starts from the initial choice of varieties that are planted, to the way they are grown, harvested, processed, packaged, transported, traded and displayed.

Our food originates from a rich pool of diverse and constantly evolving species and varieties. These plants are not only part of our culinary heritage but also essential for the future of agriculture. Currently we only utilize a tiny spectrum of the varieties that still exist and we only eat a fraction of the harvest. Much of it is wasted, often due to purely cosmetic marketing standards. With it we also waste the energy, labor and resources that were spent to grow the produce in the first place. Because our food system is globalized, the way we handle food has consequences that reach far beyond our directly perceived surroundings.

This short guide will shine some light on why our food system has become obsessed with perfection, and how this affects our food culture, farmers and planet.

The Industrialization of Agriculture

During the Green Revolution of the 1960’s, people tried to apply the same methods and mechanisms that previously drove the industrial revolution to agriculture. In order to do so agriculture had to become an automated process and the cultivars (cultivated plant varieties) it used needed to become standardized.

To boost productivity, so called HYVs (High Yielding Varieties) were developed. HYVs can be grown in a wide variety of climatic and geographic regions, but are heavily dependent on external inputs, such as fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation. HYVs were used globally to replace thousands of diverse, traditional, locally adapted varieties. A one-size-fits-all approach to agriculture inadvertently led to the extinction of many cultivars that were developed over the course of history. A vast majority of all varieties developed by humans have already become extinct during the last 50 years.

Today the remaining agricultural diversity is stored frozen in time at international genebanks and kept alive through cultivation by dedicated gardeners and smallholder farms, many of them in the global South.

Hybrid Seeds, GMOs and Patent Enforcement

Today the seed market is dominated by so called F1 Hybrids. These are created from two different lines of plant cultivars that are developed for specific qualities, such as size and pest resistance. The two lines are crossbred to create a hybrid that, in its first generation, expresses the superior qualities of both lines and grows especially vigorously. However, subsequent generations become unstable and lose the beneficial qualities of the first generation. This means it is useless to save seeds from a hybrid variety - it essentially has built in copyright protection. The farmer must repurchase the seed every year and becomes dependent on the breeder. He also loses the ability to develop the cultivar over time. Hybrids cannot adapt, evolve or diversify on the farm, in contrast to non-proprietary, open pollinated varieties.

There are many other examples of how the industry makes farmers dependent on its seeds, thereby inhibiting diversification. One is the so called ‘terminator technology’ used in select genetically modified plants, which renders their seeds infertile. Another is the strict enforcement of seed patents by suing farmers who are found to have saved and regrown corporation owned seeds.

Monocultures and Monopolies

Over the past decades a few large agrochemical corporations have bought up smaller seed companies in order to control the market. The corporations discontinued existing seed lines of these companies in order to cut costs and to promote their own cultivars, along with the chemical fertilizers and pesticides, which are sold by the very same corporations. Today a large percentage of the industrial food system relies on just a few cultivars that are planted as monocultures on a massive scale. In 2013 the global seed and pesticide market was dominated by just six companies (Syngenta, Bayer, BASF, DOW, Monsanto and DuPont) that, together, controlled 63% of the commercial seed market and 75% of the global pesticide market 1. Some of these companies are currently in the process of merging with others to gain an even bigger share of the market.

One hurdle that prevents diverse plant varieties from entering the market are cultivar registration procedures, which are very costly and time consuming. Small breeders and farmers, who wish to plant and sell local, traditional varieties, can rarely afford the costs of registering their seeds, because these often are niche products that don’t generate enough money to cover the costs of registration.

1 ETC Group. Breaking Bad: Big Ag Mega-Mergers in Play. 2015

Trade Norms

In order to regulate and simplify the international trade of produce, governments have implemented trade norms that specify exactly how a fruit or vegetable has to look. The EU recently dropped many of these criteria (regulations for apples, pears, tomatoes, citrus fruits and others are still in place 2), but traders and retailers still stick with the norms or impose their own secret standards. A strict ‘quality’ control system is in place to filter the harvest. Fully automated sorting machines are used on the farm to find and discard even slight variations. Hand tools for checking fruit and vegetable samples, such as color swatches and stencils to measure shape and size are used in the distribution centers. A perfect cauliflower, for example, must measure 15 cm in diameter and weigh 1 kilogram. Whole truckloads can be rejected if individual samples turn out to be deviant. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, up to 20% of production 3 is wasted mostly due to post-harvest fruit and vegetable grading caused by quality standards set by retailers.

Dependence on costly high tech sorting machines to facilitate the grading process also puts small and biodiverse farms at a disadvantage.

2 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 543/2011. 2011

3 FAO. Global food losses and food waste. 2011

Automation, Transport and Artificial Growing Environments

The automation of agricultural processes such as planting, harvesting, processing and packaging only works with cultivars of very specific shapes, sizes and qualities. For example, long, skinny french fries can only be cut out of large uniform potatoes. Tomatoes need to have a tough skin in order to cope with being harvested with heavy machinery.

With a large amount of produce being traded globally, logistics have a large influence on what kind of produce is being grown. Uniform fruit can be transported more efficiently, because it facilitates the use of standardized packaging and stacking methods. Long distances of shipping also mean that only a few durable cultivars are used.

Produce is often grown in ultra-controlled artificial environments, such as hydroponic solutions in greenhouses. The environmental effects on the growth of these plants, like differing soil and weather conditions are taken out of the equation. Plants that are bred and grown under these consistent conditions do not evolve and adapt anymore. They are no longer subject to evolutionary pressures.

Processed Food, Blurred Seasonality and Branding

The rapid decline of agricultural biodiversity is masked by the enormous increase of processed foods and imports of new exotic fruits and vegetables. Instead of recognizing the impoverishment of our food supplies, we are given the impression of a massive increase in the diversity and choice of the food we buy. Processed food often relies on only a small number of species that are transformed into a seemingly infinite variety of products. The constant availability of any type of fruit or vegetable from greenhouse farming and food imports also contributes to the idea that the quality of produce needs to be predictable and consistent. Consumers have become accustomed to this monotonous stability. Fruits and vegetables are expected to be as consistent as factory made mass products. In fact, the consistent shape and color of particular fruits and vegetables fulfill the same purpose as the color and design of trademarks or brands.

The Hunt for Perfection

At the end of the industrial food chain, is the consumer. We have become increasingly detached from the processes of food production. Many have forgotten or have never experienced the ways fruits and vegetables can actually look. Retailers and advertisements heavily influence our perception on what is good to eat and what is not. We predominantly use vision rather than smell and taste to judge our food. The more familiar a fruit or vegetable looks, the more likely we are to pick it up. The more consumers get used to the uniformity that is presented in supermarkets the more they are repelled by variation and the more difficult it becomes, in turn, to market fruits and vegetables that don’t look the way we think they should. The effects of this hunt for perfection trickle down the food chain from retailer to trader to farmer to breeder and back to the consumer. The food system is caught in a redundant cycle that causes produce to become increasingly more consistent.

Why it’s good to eat Wonky Fruits and Vegetables

Nothing is more impactful in transforming our planet than agriculture. Depending on how we practice agriculture, it can be a constructive or a destructive force. We currently overproduce and globally waste one third of the food we grow. In the process we poison our rivers, erode our soil, deplete our resources and extinguish biodiversity.

Appreciating and eating unusual looking fruits and vegetables can do real good on many levels. It helps to reduce food waste and overproduction. It promotes the return of diversity to agriculture and the use of regionally adapted and open pollinated varieties. It reduces agriculture’s dependence on external inputs such as irrigation, fertilizers and pesticides. It gives advantage to regional farms over long distance trade, and promotes bulk sales over standardized plastic packaging (fruit and veg already has its own natural packaging). And after all, wonky fruits and vegetables are no less nutritious or delicious than their ‘perfect’ counterparts.

EAT WONKY!

Introduction

Fruits and vegetables that don’t fit our established norms are filtered out and avoided in every stage of our food-system. It starts from the initial choice of varieties that are planted, to the way they are grown, harvested, processed, packaged, transported, traded and displayed.

Our food originates from a rich pool of diverse and constantly evolving species and varieties. These plants are not only part of our culinary heritage but also essential for the future of agriculture. Currently we only utilize a tiny spectrum of the varieties that still exist and we only eat a fraction of the harvest. Much of it is wasted, often due to purely cosmetic marketing standards. With it we also waste the energy, labor and resources that were spent to grow the produce in the first place. Because our food system is globalized, the way we handle food has consequences that reach far beyond our directly perceived surroundings.

This short guide will shine some light on why our food system has become obsessed with perfection, and how this affects our food culture, farmers and planet.

The Industrialization of Agriculture

During the Green Revolution of the 1960’s, people tried to apply the same methods and mechanisms that previously drove the industrial revolution to agriculture. In order to do so agriculture had to become an automated process and the cultivars (cultivated plant varieties) it used needed to become standardized.

To boost productivity, so called HYVs (High Yielding Varieties) were developed. HYVs can be grown in a wide variety of climatic and geographic regions, but are heavily dependent on external inputs, such as fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation. HYVs were used globally to replace thousands of diverse, traditional, locally adapted varieties. A one-size-fits-all approach to agriculture inadvertently led to the extinction of many cultivars that were developed over the course of history. A vast majority of all varieties developed by humans have already become extinct during the last 50 years.

Today the remaining agricultural diversity is stored frozen in time at international genebanks and kept alive through cultivation by dedicated gardeners and smallholder farms, many of them in the global South.

Hybrid Seeds, GMOs and Patent Enforcement

Today the seed market is dominated by so called F1 Hybrids. These are created from two different lines of plant cultivars that are developed for specific qualities, such as size and pest resistance. The two lines are crossbred to create a hybrid that, in its first generation, expresses the superior qualities of both lines and grows especially vigorously. However, subsequent generations become unstable and lose the beneficial qualities of the first generation. This means it is useless to save seeds from a hybrid variety - it essentially has built in copyright protection. The farmer must repurchase the seed every year and becomes dependent on the breeder. He also loses the ability to develop the cultivar over time. Hybrids cannot adapt, evolve or diversify on the farm, in contrast to non-proprietary, open pollinated varieties.

There are many other examples of how the industry makes farmers dependent on its seeds, thereby inhibiting diversification. One is the so called ‘terminator technology’ used in select genetically modified plants, which renders their seeds infertile. Another is the strict enforcement of seed patents by suing farmers who are found to have saved and regrown corporation owned seeds.

Monocultures and Monopolies

Over the past decades a few large agrochemical corporations have bought up smaller seed companies in order to control the market. The corporations discontinued existing seed lines of these companies in order to cut costs and to promote their own cultivars, along with the chemical fertilizers and pesticides, which are sold by the very same corporations. Today a large percentage of the industrial food system relies on just a few cultivars that are planted as monocultures on a massive scale. In 2013 the global seed and pesticide market was dominated by just six companies (Syngenta, Bayer, BASF, DOW, Monsanto and DuPont) that, together, controlled 63% of the commercial seed market and 75% of the global pesticide market 1. Some of these companies are currently in the process of merging with others to gain an even bigger share of the market.

One hurdle that prevents diverse plant varieties from entering the market are cultivar registration procedures, which are very costly and time consuming. Small breeders and farmers, who wish to plant and sell local, traditional varieties, can rarely afford the costs of registering their seeds, because these often are niche products that don’t generate enough money to cover the costs of registration.

1 ETC Group. Breaking Bad: Big Ag Mega-Mergers in Play. 2015

Trade Norms

In order to regulate and simplify the international trade of produce, governments have implemented trade norms that specify exactly how a fruit or vegetable has to look. The EU recently dropped many of these criteria (regulations for apples, pears, tomatoes, citrus fruits and others are still in place 2), but traders and retailers still stick with the norms or impose their own secret standards. A strict ‘quality’ control system is in place to filter the harvest. Fully automated sorting machines are used on the farm to find and discard even slight variations. Hand tools for checking fruit and vegetable samples, such as color swatches and stencils to measure shape and size are used in the distribution centers. A perfect cauliflower, for example, must measure 15 cm in diameter and weigh 1 kilogram. Whole truckloads can be rejected if individual samples turn out to be deviant. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, up to 20% of production 3 is wasted mostly due to post-harvest fruit and vegetable grading caused by quality standards set by retailers.

Dependence on costly high tech sorting machines to facilitate the grading process also puts small and biodiverse farms at a disadvantage.

2 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 543/2011. 2011

3 FAO. Global food losses and food waste. 2011

Automation, Transport and Artificial Growing Environments

The automation of agricultural processes such as planting, harvesting, processing and packaging only works with cultivars of very specific shapes, sizes and qualities. For example, long, skinny french fries can only be cut out of large uniform potatoes. Tomatoes need to have a tough skin in order to cope with being harvested with heavy machinery.

With a large amount of produce being traded globally, logistics have a large influence on what kind of produce is being grown. Uniform fruit can be transported more efficiently, because it facilitates the use of standardized packaging and stacking methods. Long distances of shipping also mean that only a few durable cultivars are used.

Produce is often grown in ultra-controlled artificial environments, such as hydroponic solutions in greenhouses. The environmental effects on the growth of these plants, like differing soil and weather conditions are taken out of the equation. Plants that are bred and grown under these consistent conditions do not evolve and adapt anymore. They are no longer subject to evolutionary pressures.

Processed Food, Blurred Seasonality and Branding

The rapid decline of agricultural biodiversity is masked by the enormous increase of processed foods and imports of new exotic fruits and vegetables. Instead of recognizing the impoverishment of our food supplies, we are given the impression of a massive increase in the diversity and choice of the food we buy. Processed food often relies on only a small number of species that are transformed into a seemingly infinite variety of products. The constant availability of any type of fruit or vegetable from greenhouse farming and food imports also contributes to the idea that the quality of produce needs to be predictable and consistent. Consumers have become accustomed to this monotonous stability. Fruits and vegetables are expected to be as consistent as factory made mass products. In fact, the consistent shape and color of particular fruits and vegetables fulfill the same purpose as the color and design of trademarks or brands.

The Hunt for Perfection

At the end of the industrial food chain, is the consumer. We have become increasingly detached from the processes of food production. Many have forgotten or have never experienced the ways fruits and vegetables can actually look. Retailers and advertisements heavily influence our perception on what is good to eat and what is not. We predominantly use vision rather than smell and taste to judge our food. The more familiar a fruit or vegetable looks, the more likely we are to pick it up. The more consumers get used to the uniformity that is presented in supermarkets the more they are repelled by variation and the more difficult it becomes, in turn, to market fruits and vegetables that don’t look the way we think they should. The effects of this hunt for perfection trickle down the food chain from retailer to trader to farmer to breeder and back to the consumer. The food system is caught in a redundant cycle that causes produce to become increasingly more consistent.

Why it’s good to eat Wonky Fruits and Vegetables

Nothing is more impactful in transforming our planet than agriculture. Depending on how we practice agriculture, it can be a constructive or a destructive force. We currently overproduce and globally waste one third of the food we grow. In the process we poison our rivers, erode our soil, deplete our resources and extinguish biodiversity.

Appreciating and eating unusual looking fruits and vegetables can do real good on many levels. It helps to reduce food waste and overproduction. It promotes the return of diversity to agriculture and the use of regionally adapted and open pollinated varieties. It reduces agriculture’s dependence on external inputs such as irrigation, fertilizers and pesticides. It gives advantage to regional farms over long distance trade, and promotes bulk sales over standardized plastic packaging (fruit and veg already has its own natural packaging). And after all, wonky fruits and vegetables are no less nutritious or delicious than their ‘perfect’ counterparts.

EAT WONKY!

Special thanks to Zachraň jídlo.

Zachraň jídlo (Save Food) is a group of activists that stirs up a debate about food waste in the Czech Republic. They aim to provide information, education and solutions to all participants in the production, distribution and consumption of food. Zachraň jídlo points out social, economic and environmental impacts of food waste and raises public awareness. In June 2016 the group launched a campaign called Jsem připraven (I’m Ready) promoting wonky fruits and vegetables.

www.zachranjidlo.cz/en

Zachraň jídlo (Save Food) is a group of activists that stirs up a debate about food waste in the Czech Republic. They aim to provide information, education and solutions to all participants in the production, distribution and consumption of food. Zachraň jídlo points out social, economic and environmental impacts of food waste and raises public awareness. In June 2016 the group launched a campaign called Jsem připraven (I’m Ready) promoting wonky fruits and vegetables.

www.zachranjidlo.cz/en

All content © Uli Westphal. Please respect the copyright.